When we teach children to be emotionally literate we are teaching them to problem solve so that they never find themselves in the position of ‘not knowing what to do when they don’t know what to do!’

When in this situation people often freeze, they may run away from the situation, avoid thinking about the problem or perhaps behave badly in order to create a distraction from the real issue, which is, that they don’t know what to do. Most importantly and understandably they don’t want to look foolish and become a figure of fun. Children are no different.

When in this situation people often freeze, they may run away from the situation, avoid thinking about the problem or perhaps behave badly in order to create a distraction from the real issue, which is, that they don’t know what to do. Most importantly and understandably they don’t want to look foolish and become a figure of fun. Children are no different.

People panic and children panic! For this reason, it is helpful if we teach children as early as possible to self-soothe. That is, to use their THINKING and acknowledge their FEELING of panic. Panic is fear and we can only be frightened of things that we don’t understand or have no knowledge of. So the task that the child needs to undertake is to gather information about the fearful situation.

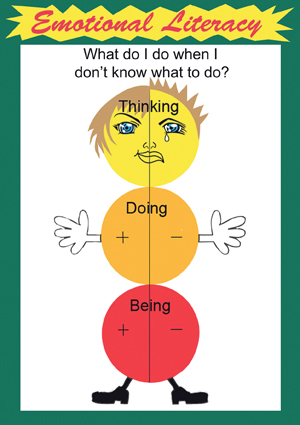

Once the feeling is named, the child can start to think about what needs to be done to stop the fear. With reference to the diagram at the top of the page, the double headed arrow between FEELING and THINKING indicates that once children are starting to feel comfortable with the process of emotional literacy they move between the two positions. They do this until they are certain that they have named their feeling accurately.

Another skill the child needs to acquire at this time is recognising the body sensation that accompanies their feeling. The reason being, that this skill becomes the early warning system for the child in the future. As an example, they may feel ‘goose bumps’ when they are frightened, but if they’re not cold, then they can in time come to understand that there body is telling them something. Sometimes, feelings we have are outside of our awareness and we don’t recognise them until we are in the middle of, say, a panic attack so the early warning system is extremely important to help us avoid unnecessary stress.

You may wonder why learning to recognise and name facial expressions isn’t sufficient to give children the skills they need. Indeed, reading facial expressions is part of human communication but if someone is smiling broadly at a child while encouraging them to do something they don’t want to do how will the child protect themselves? If they aren’t clear about their own feelings, can’t understand quite what’s happening and don’t know how to get help then they are extremely vulnerable.

There are others who hide behind a ‘public face’ and can’t form close relationships or ask for help when they need it. These are just two examples of how emotional illiteracy presents and as responsible adults we wouldn’t want either of the above for our children. We need them to be able to build healthy relationships and learn how to keep themselves safe and that’s what emotional literacy gives them.

There are others who hide behind a ‘public face’ and can’t form close relationships or ask for help when they need it. These are just two examples of how emotional illiteracy presents and as responsible adults we wouldn’t want either of the above for our children. We need them to be able to build healthy relationships and learn how to keep themselves safe and that’s what emotional literacy gives them.

When the emotional literacy process is in motion the child will start to feel grounded and more confident and as a result will be able, initially with support, to start problem solving in a variety of situations. They can learn to organise the information they have in order to pin down what they don’t know. For instance, they may have pen, pencils and paper and can read or have an adult read the given information and question to them. They can then start to think about what further information they need to answer the question and how they can acquire it.

For any problem solving the child needs a starting point, a way to get them from A to B. A plan could be useful, a time line might help and enlisting the help of another child or adult could be even better.

For any problem solving the child needs a starting point, a way to get them from A to B. A plan could be useful, a time line might help and enlisting the help of another child or adult could be even better.

The last option can be troublesome if the child isn’t confident about how to approach others with a request so I have ‘rehearsals’ with my pupils. We consider the vocabulary that we might use; who would be the best person for the job and who would the child feel most comfortable working with. During this type of work I have an Emotional Literacy Floor Sheet in the room so that the child can check out its feeling and thinking as we work.

Emotional literacy can be introduced to children as early as age three by inviting them to concern themselves with the wellbeing of their favourite toy. For example, I may ask a little one how their teddy bear feels today, and young as they are, they will know some ‘feeling’ words. They may tell me that the bear feels sad, angry or frightened so I ask what the bear would need to help them feel better.

Emotional literacy is a major part of early development and we fail badly when we don’t ensure that the process is in place for every child. Through emotional literacy children become autonomous and are then able to make considered decisions about how they live their lives. There are children who, through no fault of their own, seem not to know what they want to do so finally follow what others do or find themselves in a position of doing what others wish them to do. How can they thrive in such situations?

I am aware that an investment of time is needed to teach children how to organise themselves and their thinking and also to recognise and name their feelings and body sensations. But it is an investment worth making for the wealth of benefits it will bring. Not only will academic standards rise but the impact on children’s mental health will be enormous.

Once we are emotionally literate we have a ‘toolkit’ for life. It is as important as learning to speak and read and as responsible adults we need to ensure that every child has the toolkit.

M +44 (0)7771 698075

mail@antheaharding.co.uk

www.antheaharding.co.uk